Imagine this scenario…

You receive a MIO from a student that they’re hoping to talk to you before class. Maybe you’ve noticed that they seem distracted lately, or that they’ve been absent more frequently than usual. Maybe you haven’t noticed anything at all. You find them waiting outside your office. They come into the room and you notice their hands are shaking. They start by telling you they’ve been struggling and are hoping for an extension on their paper. They go into their story and begin sharing with you their experiences of sexual violence.

What do you do? How should you respond?

*Disclaimer, any likenesses to real persons is unintentional. Although this narrative has been inspired by real teachers and students, it does not reflect the stories of any specific person(s).

Sexual Violence and Post-Secondary Education

Bill 151, An Act to prevent and fight sexual violence in higher education institutions, was created by the Quebec government in response to the fact that 15-24 year olds are the most likely age group to experience sexual violence, and student status is seen as a key risk factor (Conroy & Cotter, 2017). Roughly 20% of female post-secondary students; as many as 50% of trans, gender-queer, and non-binary students; and almost 7% of male students express experiencing sexual violence in their lifetimes, with half of those experiences happening during their school careers (AAU, 2017; Schwartz, Z. 2018; CFS , 2015; DeKeseredy & Kelly. 1993; UofA Sexual Assault Centre. 2001; Sabina, & Ho, 2014). Now imagine the students in your classes. It’s very likely that one or more of them has recently experienced sexual violence.

Each one of these students will be affected differently by their experiences, and each will know best what they need in its wake. Sexual violence is just one aspect of their lives; they are also passionate students, caring family members and friends, dedicated workers, engaged community members, and vibrant people. As educators, we have the privilege to walk alongside many of them through emerging adulthood, witnessing as they develop who they are and the trajectory of their lives. We can all play a role in how these chapters of their stories are written, and we have a responsibility to ensure that their experiences at Vanier contribute positively to their lives, and do not compound trauma. This article aims to help teachers feel better equipped to support students struggling in the wake of an experience of sexual violence.

Sexual Violence Prevention and Response at Vanier

To fulfill our legal obligations to Bill 151 and address this need, Vanier has created its Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Official Policy & Procedural Document. Along with a team of people in Student Services and the policy’s Standing College Committee, as the Social Service Officer for Sexual Violence Prevention and Response (SSO-SVPR) I am responsible for providing direct support, outreach, education, and coordinating this policy’s implementation at Vanier.

Sexual violence robs an individual of choices. Through the collective efforts of the Vanier College community putting this policy into action, we are trying to facilitate a survivor/victim’s ability to make choices that re-establish some equity and sense of justice, so that students affected by sexual violence have the same opportunity to succeed in their studies as other students. The policy defines a survivor/victim as a “Person who has experienced sexual violence. Personal, cultural, and socio-political reasons may influence a person in self-identifying with either term, survivor or victim” (Vanier College, 2018, p. 6). We affirm their right to choose the word that best fits for them; both terms are used throughout the policy.

All of the students I’ve met as a part of my work providing support are striving to do well in their studies, despite the significant impacts of their experience. Some of the impacts on their lives might include difficulty concentrating, mentally reliving what happened to them, hypervigilance, reactivity or numbing, and difficulty managing big emotional responses. Teachers are an important bridge between these students and our services. They see these students on a regular basis and can also direct them to supports or resources if they become aware that one of their students has experienced sexual violence. Compassionately responding to disclosures and facilitating referrals to specialized services offer students with choices to meet their needs. These achievable interventions can make a huge difference in their lives.

Teachers play a crucial role in a few other key ways. They can teach using trauma-informed school practices, including how they broach the topics of rape or rape culture in their classrooms, if they choose to discuss them. They can also support academic accommodations for their students, by collaborating to see how a student’s identified needs can be reasonably accommodated within the pedagogical context of the course.

Trauma-Informed School Values

• feelings of physical, social, and emotional safety in students

• a shared understanding among staff about the impact of trauma and adversity on students

• positive and culturally responsive discipline policies and practices

• access to comprehensive school mental and behavioral health services

• effective community collaboration

(CPI, 2018; NASP, 2016)

The Scope of a Teacher’s Roles and Responsibilities

A teacher does not have to be a jack-of-all-trades. The Vanier community collaborates as a holistic unit to support all students. If you ever feel out of your skill set or overwhelmed, Student Services is here as a specialized support for both students and teachers in this process. We have specialized education and training to support students who have experienced trauma. We are not expecting teachers to be counsellors or trained intervention professionals, and we also recognize how intimidating and overwhelming it can be to receive a disclosure. We are hoping you can connect as the empathetic and caring human being who chose to enter this profession. You don’t have to be perfect to have a big impact.

Responding to Disclosures

If you receive a disclosure, remember this set of words: Listen, Believe, Empower.

Listen

Actively and compassionately listen and respond to what you’re hearing.

Believe

Validate and normalize the person’s feelings, and assure them it’s not their fault.

Empower

Ask the person what they need right now, and connect them with resources.

Listen – When receiving a disclosure, the most important thing is to listen and create a space where you can give the disclosure your full attention. Offer a choice to the student; suggest meeting somewhere private where there won’t be any interruptions or people overhearing. Sometimes people can also feel safer near a more public space. Ask which is the right fit for them, and follow their lead.

Start by telling them you are glad they felt comfortable sharing with you what happened to them. Disclosing can bring up fears and anxiety; you might acknowledge the step that the student is taking by telling you what happened to them. You might say something like, “It takes courage to talk about this,” or “Thank you for sharing that with me.” Let the survivor/victim tell you as little or as much as they want and avoid asking for details. Discussing what happened in detail may be overwhelming or feel re-traumatizing. For some people, talking about their feelings around what happened can be as helpful as talking about the details. Take their lead on this.

What can be most comforting and affirming for survivors/victims is feeling seen and heard. This means demonstrating empathy for what the person is going through by reflecting their emotional reactions or feelings to events and showing compassion for their experiences. Encourage their disclosure by showing you’re engaged and actively listening. You could do this through nodding, or by making listening noises (like “mhmm”). Mirroring the language they use to describe the events or themselves, or paraphrasing can be other ways to demonstrate respect and care for their perspective. For example, “what I hear you saying is…”.

Avoid minimizing or expressing judgment for what happened to them. Never respond in a way that highlights how “it could have been worse” or that they’re “lucky nothing more happened to them” or “they should be over this by now.” The impact that sexual violence has on a person is very personal and shouldn’t be ranked or rated. Showing compassion for someone’s experiences doesn’t lessen the amount we have for others but grows our capacity for it.

Believe – This empathy can go a step further by validating and normalizing the survivor/victim’s responses. You could say something like, “It makes sense that you feel this way,” or, “It is okay to feel angry/confused/sad/scared…” to reassure them that these are understandable and common reactions to this type of experience.

Victim blaming and shaming and other behaviours that foster fears of not being believed are some of the biggest barriers for people reaching out for support. Many sexual assault survivors/victims struggle with blaming themselves. One of the most damaging things we can do would be to blame, judge, or not believe our students, especially if we’re the first person they have told. You could offer reassurance that what happened to them was not their fault. (“I believe you,” or “It’s not your fault.”) To convey that they are not alone in what they’re experiencing, you might reassure the person that, if they would like your help, together you will try to do whatever is possible to get the support they are seeking.

It is worth acknowledging that some people express discomfort in ‘believing’ survivors/victims as they feel it means they are not impartial, or it might look like they are taking sides. However, should someone be telling you something of such significance, it is because they trust you as a person in authority who can somehow help them. All of the teachers I have met so far take their responsibility to help seriously and know that it is not a teacher’s role to judge the veracity or significance of what happened to a student. Should they have any concerns around their ability to receive a disclosure, teachers can refer the student to the Sexual Violence Response Team (SVRT) in Student Services. You might offer “I’m here to listen and support you, and it would be helpful for you to talk to someone who has specialized knowledge in this area,” or “I would be happy to go with you to talk to someone,” or “There are places that you can go to get information or confidential support.” If it is needed, any documentation required, especially as it relates to academic accommodations, will be handled by our sexual violence specialized service.

Empower – The most important role we can play is supporting the decisions the person makes about their needs, even if we might behave differently given the same circumstances. Work together to identify their immediate needs, figure out the person’s next steps and reassure them that they have control of their decisions. Connect them with supports and resources to address the needs they feel are most important to them. They may already have psychological, social or emotional support. Our role could be small, or large, depending on their access to services and support systems. It is always one part of a bigger picture in their lives.

In responding to a disclosure of sexual assault, we also want to promote empowerment of the survivor/victim. Sexual assault can result in a sense of loss of power and control. When discussing their options moving forward, you can support the person in exerting control over their lives by trusting them to make choices about what to do next—choices that place their health and wellbeing at the forefront.

If it’s appropriate, explore with them their social supports (e.g. family, friends, and professionals), and help them connect with them. Make referrals to Vanier support services or other sexual violence support services in their community. If they say they would find it helpful, support them in accessing these services by calling ahead or accompanying them to Student Services. If they express reluctance to talk with other people, you can call a member of the SVRT for consultation on how to proceed or which resources you can provide.

Finally, if talking about sexual violence feels uncomfortable for you, practice role playing these scenarios with a colleague, or a member of the SVRT. It takes practice to be able to talk about, let alone receive disclosures of trauma and our own experiences can often impede our ability to be fully present or dictate our reaction. Practicing these discussions can limit reactions that can be unhelpful or even harmful, such as shock or alarm, or shutting down and dismissing someone without fully hearing them. The way a disclosure of sexual violence has been received can have either positive or detrimental impacts in a survivor/victim’s healing journey, and preparation can go a long way in ensuring you are promoting trust and safety.

Direct Support Services for Sexual Violence at Vanier

Vanier Sexual Outreach and Support (VSOS) is Vanier’s hub for sexual violence response service, which also offers outreach and education related to healthy sexuality and the prevention of sexual violence. The One-Stop Service, staffed by the Sexual Violence Response Team (SVRT) at Student Services, is one branch of VSOS’s programming that provides direct support and responses from the College following incidences of sexual violence.

Depending on the needs and resources of the person, we may be able to offer them:

Supports and Responses Offered by VSOS

• Case Management

• Emotional Support

• Accommodations

• Advocacy & Accompaniment

• Assisted Referrals

• Information

• Informal and Formal Responses from the College – including facilitated education, and other complaint processes

Referrals

Every individual in Canada, including teachers, who receives a disclosure of sexual violence from an underage person, has a responsibility to report it to the Director of Youth Protection to ensure their safety and the safety of others (suspected sexual abuse of children and persons under the age of 18). How this happens can be informed by the student; if they are interested, you may work alongside them to submit the report. If you would like support in filing a report with DYP in a way that’s sensitive to students’ needs, you can come to Student Services.

Acknowledging the potential deleterious effects of sexual violence, survivors/victims can be granted academic accommodations to help them succeed in their studies. If a student wants to directly disclose their academic accommodations needs to a teacher, we affirm their right to do so. Teachers are encouraged to offer referrals to our services so that students are aware of these supports on campus. However, we will never mandate a student to visit with these supports or place their accommodation requests through these mechanisms, if that is not what they want. Regardless of whether or not a student wants to visit our support services, we can also provide anonymous support to teachers so that they can pass along resources and information to their students, if they feel comfortable doing so.

Some students may want to keep their experiences of sexual violence separate from the classroom experience, thereby protecting their classroom relationships. Having the knowledge that their teachers don’t know what happened to them can be incredibly important to being able to concentrate, feeling more like themselves, and not feeling defined by what happened to them following incidents of sexual violence. To facilitate the communication of a student’s accommodation needs, VSOS may reach out to teachers directly.

If a student comes to a teacher but feels uncomfortable explaining the reasoning behind their need for an academic accommodation or extra support, teachers are encouraged to provide an assisted referral by calling Student Services and asking for a member of the Sexual Violence Response Team. We will try to accommodate an assisted referral where the teacher walks the student down to Student Services, or we can set up a time to meet with the student later. We will then coordinate with the teacher to communicate the student’s accommodation needs later.

How do we support survivors/victims in the weeks and months to come, or survivors/victims of historical violence? Would they prefer if you checked in with them periodically or would they prefer to bring it up if they want to talk about it with you? Assess what amount and what kind of support you are able and willing to give. You are not a therapist or professional support person; it’s not your job to be in constant support mode. Set the boundaries you need to set. Don’t focus only on their traumatic event/history. No one wants to be in ‘survivor’ or ‘victim’ mode all the time.

Seeking out self and community care after receiving a disclosure of sexual violence can be vital for avoiding vicarious trauma and sitting with the emotional discomfort that can be associated with receiving one, such as not knowing what happens to that student afterwards. Processing this is important and might look like visiting your personal therapist, debriefing your own experiences with colleagues without sharing the student’s story, coming into the Respect Works or another member of the SVRT’s offices to talk, or finding another avenue that fits your needs. Keep in mind that unless you are debriefing with someone who is bound by confidentiality (such as a therapist or the Respect Works Officer), it is imperative not to reveal names or any identifying information about the survivor/victim who disclosed to you.

Vanier College’s Approach

Teachers are one piece of a bigger picture at Vanier. They help in setting the tone by fostering empathy and facilitating support for members of our community that have experienced sexual violence. They can also model how to facilitate discussions (including class discussions) related to rape culture in a compassionate way. Vanier will also be introducing strategies in a multi-tiered public health approach that will evolve and grow over time to decrease the prevalence of sexual violence amongst our student body.

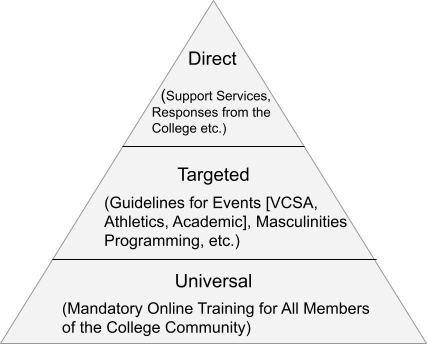

Among the offerings to come are universal prevention strategies for all members of the Vanier community, including mandatory online training for all staff, students and faculty on the topics of consent, responding to disclosures, and active bystander interventions. Targeted prevention and response initiatives to address instances where a higher risk or need is present will be implemented. These include guidelines for orientation events, events in the first 8 weeks of the semester, or events where alcohol is present. Finally, direct services to mitigate the impact of sexual violence have already been put in place. There are ways that teachers can be involved at all three levels, if they would like to support these efforts.

At the universal and targeted levels, teachers can contribute to College initiatives to shift its culture towards one that instills consent practices and disrupts norms that enable sexual violence. Since starting at Vanier, I have been impressed by the number of academic festivals and fairs here that have covered the topic of consent or gender-based violence with care and sensitivity, helping to shift our culture in positive ways.As educators, we have a legal and moral responsibility: when classroom content touches on rape culture or sexual violence, we must work to foster empathy and equip students with tools to make consent an important part of sexual encounters. We must also decrease barriers for survivors/victims of sexual violence who are seeking support. As an educational institution, we set the tone for how these issues are addressed; our actions shape students’ perceptions of these topics.

Next Steps

If you would like to learn more about VSOS or the efforts happening related to sexual violence, feel free to reach out to me (ext. 7145 – C203-B) or another member of the SVRT. We will be continuing to roll out education and outreach on preventing and responding to sexual violence. This includes upcoming mandatory yearly online training for College employees.

Finally, I would like to extend a special thanks to the UBC AMS Sexual Assault Support Centre who have very graciously offered me their continued knowledge, support and workshop content, which directly informed parts of this article.

Lindsay Cuncins

is the Social Service Officer for Sexual Violence Prevention and Response (SSOSVPR) in Student Services.

References:

AAU (2017). Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct Retrieved from https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/AAU-Campus-Climate-Survey-FINAL-10-20-17.pdf

Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) (2015). Sexual Violence on Campus, Retrieved from https://cfs-fcee.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Sexual-Violence-on-Campus.pdf

Conroy, S. & Cotter, A. (2017). Self-reported sexual assault in Canada, 2014. StatsCan. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14842-eng.htm

CPI (2018). How Trauma Informed Schools Help Every Student Succeed. Retrieved from https://www.crisisprevention.com/en-CA/Blog/October-2018/Trauma-Informed-Schools

DeKeseredy and Kelly. (1993). The Incidence and Prevalence of Woman Abuse in Canadian University and College Dating Relationships: Results From a National Survey.

National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) (2016). Trauma-Sensitive Schools. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/mental-health/trauma-sensitive-schools

Sabina, C., & Ho, L. Y. (2014). Campus and College Victim Responses to Sexual Assault and Dating Violence: Disclosure, Service Utilization, and Service Provision. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(3), 201–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014521322

Schwartz, Z. (2018). Canadian universities are failing students on sexual assault Retrieved from https://www.macleans.ca/education/university/canadian-universities-are-failing-students-on-sexual-assault/

University of Alberta (UofA) Sexual Assault Centre. (2001). A Survey of Unwanted Sexual Experience Among University of Alberta Students.

Vanier College. (Nov. 20th, 2018). Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Official Policy & Procedural Document. Retrieved from http://www.vaniercollege.qc.ca/bylaws-policies-procedures/files/2018/11/Sexual-Violence-Prevention-Response-Official-Policy-Procedural-Document-Approved-November-20-18.pdf.